Pulse

15 Sep 2025

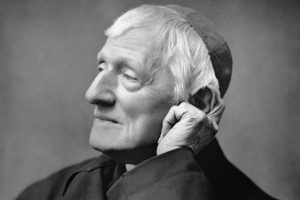

On 31st July 2025, Pope Leo XIV proclaimed John Henry Newman (1801-1890) the 38th Doctor of the Universal Church, an elevation that was enthusiastically welcomed by Roman Catholics around the world. The official promoter of the Newman cause, Oratorian Father Ignatius Harrison, spoke for many when he said,

This is going to do so much good, dare I say, in the modern world of today because of Newman’s ideas. I think this has come at just the right time. I see it as providential.

The 19th century cardinal, theologian and philosopher, who was canonized by Pope Francis on 13 October 2019, was originally an Anglican until his conversion to Roman Catholicism on 9 October, 1845.

During his long career, Newman witnessed many changes in religious opinions and trends. His oeuvre is as expansive as it is intellectually rich and spiritually profound. It spans theology, philosophy, education, sermons, devotional works, autobiography, poetry, and ecclesial polemics.

Newman’s works bridge patristic theology, modern philosophy and contemporary religious experience. His writings on truth, faith, conscience and doctrinal development are remarkably forward-thinking for his era, making him one of the most important religious thinkers of the modern age.

The standard edition of Newman’s works comprises 31 volumes, published by Longmans, Green and Co. A separate scholarly edition of his letters and diaries was published by Oxford University Press in 32 volumes.

Among his many contributions to theological debate and Christian practice are his reflections on the relationship between faith and reason. Newman’s immediate concerns were shaped by the pervasive influence of Enlightenment rationalism which promotes a reductionist understanding of reason, and a theological liberalism which submits to its dictates.

However, what Newman had to say about faith and reason has renewed relevance today, as the contemporary church (especially its evangelical expression) continues to navigate between the Scylla of fideism and the Charybdis of rationalism.

FAITH

To understand Newman’s view of faith, one must first grasp his doctrine of divine revelation. Both as an Anglican and a Roman Catholic, Newman believed that the teachings of Christianity and the Church are grounded in the revelation of God.

In his great treatise entitled An Essay on the Development of Christian Doctrine, published in 1845 just before his conversion to Roman Catholicism, Newman presented a high view of revelation. He described revelation as comprehensive, living, and real: comprehensive because it presents a master vision of reality, living because it captivates the mind, and real because its truths are independent of the mind.

At the centre of that revelation is Christ himself, whom Newman describes as the one who ‘fulfils the one great need of human nature, the Healer of its wounds, the Physician of the soul.’ Christ, for Newman, is the ‘central aspect of Christianity.’ In his Oxford University Sermons, he categorically states that the incarnation is the article on which the Church stands or falls.

As a Roman Catholic, Newman insisted that the revelation of God is found in Scripture, but not exclusively so. Tradition, for Newman, enjoys equal dignity and importance alongside Scripture. However, even in his Anglican period Newman could argue that the doctrine of the Trinity is grounded in both Scripture and tradition in his 1833 book, The Arians of the Fourth Century.

Newman also emphasized the importance of Creeds and Dogmas, which was a distinctive feature of the Oxford Movement which he led in his Anglican period. He advances what he calls the ‘dogmatical principle’ in his long battle against the theological liberalism of his day. He describes the latter as energized by ‘the antidogmatic principle and its developments.’

Creeds and dogmas are necessary because they aid the human mind to understand the coherence of revelation. In one of his university sermons, Newman explains:

Creeds and dogmas live in the one idea [i.e., the revelation] which they are designed to express, and which alone is substantive; and are necessary because the human mind cannot reflect upon the idea except piecemeal, cannot use it in its oneness and entireness, nor without resolving it into a series of aspects and relations.

What, then, did Newman mean by faith?

Firstly, faith has to do with the believer’s trusting surrender to God in a saving relationship made possible by grace. But faith also has to do with submission to the givenness of God’s word.

Commenting on the definition of faith found in Hebrews – as the ‘evidence of things not seen’ (11:1) – Newman describes faith as follows in his Lectures on Justification:

As sight contemplates form and colour, and reason the processes of argument, so faith rests on the divine word as the token and criterion of truth … By faith then is meant the mind’s perception or apprehension of heavenly things, arising from an instinctive trust in the divinity or truth of the external word, informing it concerning them.

Newman boldly underscores the distinction between faith and reason at a time when the Church was under tremendous pressure to demonstrate that what it believes is not irrational. In his Essay on Development, he argues that the texts that present the doctrine of the Incarnation teach

… the principle of faith, which is the correlative of dogma, being the absolute acceptance of the divine Word with an internal assent, in opposition to the information, if such, of sight and reason.

In his Essays Critical and Historical (1886), Newman defines faith simply as ‘the acceptance of what our reason cannot reach, simply and absolutely upon testimony.’ Faith is that which accepts as true what Scripture discloses because it is the authoritative word of God.

Newman’s understanding of faith is always ecclesial, and never individualistic or subjectivistic, established on private judgement only. As he elegantly explains in Discourses to Mixed Congregations (1850):

In the Apostles’ days the peculiarity of faith was submission to a living authority; this is what made it so distinctive; this is what made it an act of submission at all; this is what destroyed private judgement in matters of religion … Has faith changed its meaning, or is it less necessary now? Is it not still what it was in the Apostles’ day, the very characteristic of Christianity, the special instrument of renovation, the first disposition of justification, one out of three theological virtues … Since Apostolic faith was in the beginning reliance on man’s word, as being God’s word, since what faith was then such it is now, since faith is necessary for salvation, let them attempt to exercise it toward another, if they will not accept the Bride of the Lamb [the Catholic Church]. Let them, if they can, put faith in some of those religions which have lasted two or three centuries in a corner of the earth.

REASON

However, to conclude from this that for Newman faith is irrational and that reason has no role whatsoever in the Christian faith is to misunderstand him. For against the charge that faith is absurd or against reason, Newman states: ‘Faith is not the only exercise of Reason, which, when critically examined, would be called unreasonable, and yet it is not so.’

Although Newman again and again emphasizes that faith is never reducible to reason, he makes it equally clear that it is not the case that faith has no relation to or is against reason. Faith has its own rationality which is not inimical to, but which can never be equated without qualifications with general reason or logic.

‘Faith,’ Newman writes in his university sermons, ‘is the reasoning of a religious mind, or of what Scripture calls a right or renewed heart, which acts upon presumptions rather than evidence, which speculates and ventures on the future when it cannot make sure of it.’ This returns us to the importance Newman gives to trust in the authority of divine revelation.

However, in sketching out the rationality of faith, Newman is also critiquing the narrow and reductionist definition of reason that is characteristic of Enlightenment rationalism. In particular, Newman wishes to show the inadequacies of empirical reason, which is characterized by analysis and criticism, as advanced by the British empiricists – a dominant intellectual force in his day.

Theologians have too often acquiesced to the demand of empiricism to produce proof for Christianity’s claims resulting in treatises such as William Paley’s Evidences of Christianity (1794) which Newman heavily criticizes.

It is not that Newman totally disapproves of the use of proofs to establish the truth of Christianity. He argues in his university sermons that such proofs are indeed of value to those who are weak in faith as well as the strong. To the weak, ‘the varied proofs of Christianity will be a stay, a refuge, and encouragement, a rallying point for Faith.’ And to the strong they ‘are a source of gratitude and reverent admiration, and a means of confirming faith and hope.’

What Newman cautions against is the constriction of reason according to the dictates of empirical or logical rationalism. In addition, Newman argues that reason must also include experience, even that of the common person, and refuses to follow Descartes and Hume, who treat it as suspect.

In all of this, Newman is advancing a broader and more encompassing understanding of reason than afforded by Enlightenment rationalism in general and empiricism in particular. As Michael A. Dauphinais has perceptively pointed out, ‘… Newman reshapes the debate with empiricism by refusing either to idolize or to demonise empirical and logical reason.’

Newman makes the distinction between implicit reason, which he defines as ‘the original process of reasoning,’, and explicit reason, ‘the process of investigating our reasonings.’ He summarises this memorably thus: ‘all men have a reason, but not all men can give a reason.’

The historian Eamon Duffy summarises Newman’s approach well when he writes:

Newman was not here justifying irrationality, the triumph of heart over head: instead, he was proposing a different model of what human reason actually was. Instead of the simplistic Enlightenment image of rationality as a neutral weighing up of evidence until the balance tipped in favour of a conclusion, he pointed to the complex ways in which human beings actually arrive at their core convictions, in science and daily life as much as in religion.

ILLATIVE SENSE

We come, finally, to Newman’s most important concept that crowns his epistemology, namely, the illative sense. He develops this idea mainly in his 1870 treatise An Essay in Aid of a Grammar of Assent, which is the result of many years of reflection possibly beginning from as early as the 1830s.

The illative sense is that faculty of the human mind that enables it to draw reasonable and trustworthy conclusions from a convergence of probabilities, experiences, and informal reasoning, even when demonstrative proof is lacking.

In Grammar, Newman calls the illative sense variously as a ‘ratiocinative faculty,’ ‘the reasoning faculty,’ an ‘acquired habit’, a ‘higher logic’, a ‘living organon,’ a ‘personal gift,’ ‘supra-logical judgement,’ ‘judicium prudentis viri’ (the judgement of a wise person), the ‘architectonic faculty’ and ‘the power of judging and concluding, when in its perfection.’

Human beings arrive at conclusions by formal inference – that is, by reasoning deductively according to the strict rules of logic. But they also achieve certitude by real inference – that is, by a confluence of emotions, experiences, accumulated judgements, probabilities, and intuitions.

It is the latter, not the former, that characterizes the commonest way human beings think and conduct their affairs. This is true for a great number of human judgements of truth, including religious truth.

It is through the concept of the illative sense that Newman harmonizes faith and reason – reason understood not in the narrow sense of analytical logic but in the broad sense as implicit reason. In his university sermons, he explains:

Faith, then, though in all cases a reasonable process, is not necessarily founded on an investigation, argument, or proof; these processes being but the explicit form which the reasoning takes in the case of particular minds.

Again:

… the reasonings and opinions which are involved in the act of Faith are latent and implicit; that the mind reflecting on itself is able to bring them out into some definite and methodical form; that Faith, however, is complete without this reflective faculty.

Newman insists that the illative sense is not a supernatural capability that is introduced to the believer, but a natural faculty that every human being possesses. However, although it is a natural faculty, the illative sense, like every other human faculty, can and must be trained.

Even if it is not, it is involved in every human activity of thinking and making sense of reality. As Newman puts it in the Grammar, the illative sense operates ‘in the beginning, middle, and end of all verbal discussion and inquiry, and in every step of the process.’

The importance of Newman’s idea of the illative sense, especially when considered in regard to the relationship between faith and reason, is that it interrogates and challenges reductionist understandings of rationality that dismiss the relationship. Positively, it provides a rounded and holistic epistemology that avoids a fideism that excludes reason or a rationalism that distorts faith by subordinating it to reason.

CONCLUSION

In bringing this article to a conclusion, we take a quick look at the ways in which Newman’s understanding of the relationship between faith and reason address some trends endemic to contemporary Christianity.

The first broad trend that Newman’s theology addresses is fideism which is evident in some evangelical churches that take an anti-intellectualistic approach to the faith, and which puts a premium on personal experiences. Newman reminds Christians of the importance of reason’s role in the Christian faith which cannot be dismissed even as certain forms of rationalism must be rejected.

The second trend in modern theology that Newman’s epistemology addresses is certain versions of analytical theology. This especially applies to those approaches that place inordinate emphasis on propositional reasoning, logical deduction, and abstract systematization at the expense of the personal and experiential dimensions of the faith.

Newman would provide a vital corrective to these approaches by underscoring the limits of abstract reasoning in matters of the faith.

To analytic theologians who are carried away by the force of deductive reasoning, Newman would remind them of Ambrose’s arresting statement that : ‘It did not please God to save his people by means of logic’ (Non in dialectica complacuit Deo salvum facere populum suum).

To analytic theologians fond of creating Procrustean beds with their logic, resulting in the amputation of doctrines, Newman would insist that theology is grounded on the authoritative text (Scripture) and its authoritative interpreter (the Church).

Dr Roland Chia is Chew Hock Hin Professor at Trinity Theological College (Singapore) and Theological and Research Advisor of the Ethos Institute for Public Christianity.

Dr Roland Chia is Chew Hock Hin Professor at Trinity Theological College (Singapore) and Theological and Research Advisor of the Ethos Institute for Public Christianity.