Pulse

03 Nov 2025

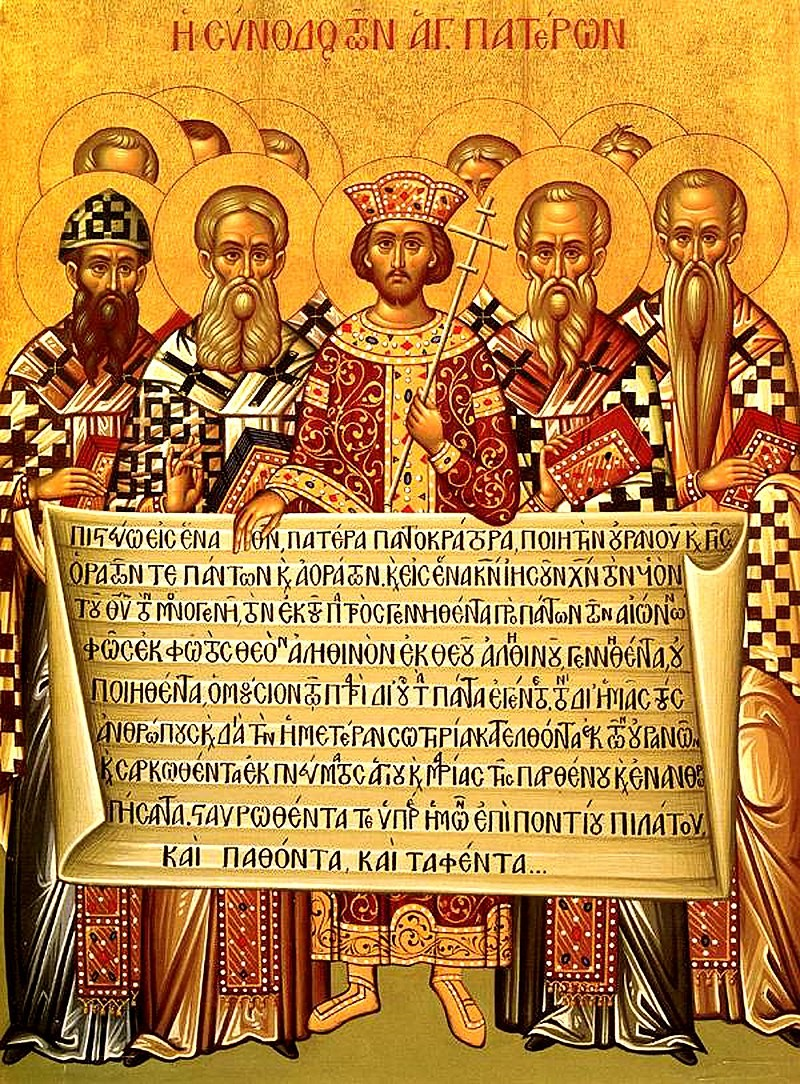

On 27 May this year (2024), the Lutheran World Federation and the Orthodox Church issued a landmark common statement on the filioque. Referring to the original version of the Nicene Creed of 325, it states that:

Valuing this old and most venerable ecumenical Christian text, we suggest that the translation of the Greek original (without the Filioque) be used in the hope that this will contribute to the healing of the age-old divisions between our communities and enable us to confess together the faith of the Ecumenical Councils of Nicaea (325) and Constantinople (381).

The Nicene Creed which is part of the Christian liturgy exists in two versions or forms.

The Eastern version of the Creed contains the original formulation which simply states that the Holy Spirit proceeds from the Father. The Western version of the Creed – which is found in the liturgies of the Roman Catholic and Protestant Churches – states that the Spirit proceeds from the Father and the Son (filioque).

This amendment to the original wording of the Creed was made in the sixth century in Spain, at about the time of the Third Council of Toledo (A.D. 587). The purpose of this change was to emphasise the equality of the Son and the Father, in an effort to deprive the Arians and the Priscillianists any loophole to establish their erroneous doctrines of the Trinity.

Both Arianism and Priscillianism teach that the Son is not of the same essence (homoousios) and co-equal with the Father.

From Spain, this revised version of the Nicene Creed which states that the Holy Spirit proceeds from the Father and the Son spread to Britain and Gaul and received the support of the Emperors of the Roman Empire, beginning with Charlemagne.

Most significantly, the filioque became a controversial and contentious issue between the Eastern and Western Churches, which subsequently contributed to the Great Schism in 1054. However, it is important to note that the filioque controversy was not the only reason for the Schism. Other factors were at play, such as the ascendency of the Byzantine Empire and the perceivable decline of Rome, the growing assertion of papal authority, and political jealousies and rivalries.

Since the schism in the 11th century, the filioque is one of the main obstacles preventing the unity of the Western and Eastern Churches. In agreeing to return to the original wording of the Nicene Creed, the LWF must surely be applauded for taking concrete steps to – as the joint-statement puts it – heal the ‘age-old divisions.’

ECCLESIASTICAL AND THEOLOGICAL OBJECTIONS

There are two reasons why the Eastern Church regarded the insertion of the filioque into the Nicene Creed as problematic, and therefore must be rejected.

The first reason may be described as ecclesiological. The Eastern Church regarded the insertion of the filioque clause as illegitimate as it did not have their concurrence. The Nicene Creed was formulated at a Council of bishops from both the Western and Eastern Churches, and any revisions to it require ecumenical consensus.

At the Council of Ephesus (431), it was agreed that any alteration of ‘the faith (or the Creed) of the Fathers assembled in Nicaea’ is strictly prohibited. The inclusion of the recitation of the ‘filioqust’ Nicene Creed in the 11th century by Pope Benedict VIII, the Patriarch of the West, without seeking consensus, angered the Eastern Patriarchs.

Some Orthodox theologians regard it as an act lacking in love and respect for the Eastern Church. The 19th century Russian theologian, Aleksey Khomyakov, has even described the act as a ‘moral fratricide.’

Without going quite as far as Khomyakov, the objection by the Eastern Church is surely reasonable and justified.

Even though Anselm of Canterbury – an eminent medieval theologian – has defended the inclusion of the filioque by arguing that regional churches must have the right to add interpretative amendments to the Creed in order to fight local heresies, the objection still stands. If churches from different regions simply took the liberty to add amendments to address local issues, the ecumenicity (and therefore authority) of the Nicene Creed would be jeopardised.

The second reason why the Eastern Church objected to the filioque is theological in nature. It is impossible to discuss the permutations and nuances of the theological debate in this brief explainer because they are too complex, not to mention convoluted. I will attempt to present the issues in broad strokes in order to give the reader an idea of the theological issues and what is at stake.

According to the Eastern Church, in the Trinity, only the Father is to be regarded as the fontal source from whom the other divine persons (i.e., the Son and the Spirit) ultimately proceed. The filioque disrupts and destroys that Trinitarian balance because it ascribes to the Son the capacity of being the origin. Consequently, the filioque does not only confuse the unique properties of the Father and the Son, it also seriously compromises the Father’s mono-principality.

The Eastern Church has also accused the West of an epistemological and methodological error. By collapsing the immanent Trinity into his economic manifestation, the West has failed to make a distinction between the eternal procession and economic sending.

Thus, the West has read the economic sending of the Spirit by the Son (John 15:26) into the triune God, which led to the erroneous conclusion that the Spirit must have proceeded also from the Son.

The theologians of the Western Church have rebutted these arguments point by point. Their arguments are too complex to discuss in any detail in this short article. Suffice to say that there are profound weaknesses in both the Eastern and Western accounts of the Trinity, particularly the Spirit’s relationship with the Father and the Son with regard to its origination (i.e., procession).

A GENEROUS ORTHODOXY

As I have stated above, I believe that the Western Church has erred in amending the Nicene Creed to include the filioque clause without the concurrence of the Eastern Church that participated in the composition of the original version.

It is therefore a laudable act on the part of the LWF to return to the original version, which does not include the 11th century amendment. It is hoped that other Protestant churches such as the Reformed church, which, like their Lutheran counterpart, has inherited the Nicene Creed from the Roman Church, would also consider doing likewise.

Although the same would be undoubtedly difficult for the Roman Catholic Church, for which the filioque has ‘achieved the status of irreversible dogma’, according to one of its most astute theologians, Avery Dulles, there is yet a way forward. In recent decades, the Roman Catholic Church, while retaining the filioque in the Latin creed, has allowed Eastern Catholics to use the eastern Creed, without the filioque.

It is hoped that the Orthodox Church could also practice the generous orthodoxy that is exemplified in the Roman Catholic Church.

The first Greek theologian who polemicized the filioque was Photius, the ecumenical patriarch of Constantinople in the ninth century. It was Photius who declared that the Western Church’s ‘excess with regard to the Spirit, or rather with regard to the entire Trinity, is not the least among their blasphemies,’ deserving a thousand anathemas.

It should be pointed out that the doctrine of the twofold procession of the Spirit was taught by a number of Western fathers both before and after Nicaea, including Tertullian, Hilary, Marius Victorinus, Augustine and Leo the Great, who was the pope at the time of the Council of Chalcedon (451).

Although the Greek Fathers were aware of the currency of the filioque in the West, none of them regarded it as heretical.

It should also be pointed out that the strict ‘monopatrist’ position (the procession of the Spirit from the Father alone) espoused by Photius and his followers was not reflective of the Eastern tradition in its entirety. Many of the Eastern fathers such as Epiphanius, Ephrem, Cyril of Alexandria, and John Damascene speak of the Spirit as proceeding from the Father through the Son.

The monopatrist position risks portraying the Son and the Spirit as autonomous, and even competing, agencies. In any case, monopatrism distances the Son from the Spirit in such a way that it is unable to give adequate account of the testimony of the NT, which describes the Holy Spirit as the Spirit of the Son (Galatians 4:6), the Spirit of Jesus (Acts 16:7), the Spirit of the Lord (2 Corinthians 3:17), the Spirit of Jesus Christ (Philippians 1:19).

The generous orthodoxy that I am advocating does not excuse the Western Church for unilaterally and thus illegitimately amending an ecumenical Creed without consulting its Eastern counterpart. Neither does it urge the Church to be slothful in its theological reflections and formulations, or to pursue a superficial irenics.

It simply urges the Church to take into account the fullness of its theological and doctrinal tradition, as it is informed and formed by God’s Word and Spirit.

Dr Roland Chia is Chew Hock Hin Professor at Trinity Theological College (Singapore) and Theological and Research Advisor of the Ethos Institute for Public Christianity.

Dr Roland Chia is Chew Hock Hin Professor at Trinity Theological College (Singapore) and Theological and Research Advisor of the Ethos Institute for Public Christianity.